Virtualizing Bluetooth Low Energy Advertisements

by NiklasWe recently merged a system-call interface for Bluetooth Low Energy advertising and scanning on Nordic nRF5x chips. This is an important step towards a stable and portable API for using Bluetooth in Tock processes. It’s significant because it addresses a tricky question: how to let multiple user processes, that don’t coordinate, each send Bluetooth advertisements.

The solution we came up with was to give each process a unique Bluetooth device address and let each control its own advertising packets, while controlling the timing of each advertisement in a kernel driver to ensure processes advertisement are isolated and avoid collisions.

In this post, I’ll give a bit of background about Bluetooth Low Energy advertisements, show a small example application, and explain the interface and implementation.

Bluetooth Low Energy Advertisements

Bluetooth Low Energy supports two types of communication channels. Connection-oriented channels are two-way communication channels between two devices that have setup a connection with tight timing constraints and, potentially, a shared encryption key. Advertising channels are for broadcast messages from lower-power devices (called advertisers) to higher-power devices (called scanners). In this post, we’re only concerned with the advertising channel.

Advertisements are typically used to broadcast messages from a low-power device, such as a beacon, to a higher-power device, such as a cell-phone. For example, iBeacon or Eddystone are commonly used application protocols for broadcasting presence. Advertisements are also used to initiate connections between devices.

An application that wishes to send Bluetooth Low Energy advertisements configures the advertising packet data and specifies how frequently it wants the advertisements to be sent (the “advertising interval”). The Bluetooth driver schedules these advertisements accordingly, with some added randomness, required by the Bluetooth specification to mitigate repeated collisions among nearby advertisers.

Each advertising packet contains a header specifying the advertisement type and length, a device address, and a data payload:

+----------+-----------+-----------+

| Header | Address | Data |

+----------+-----------+-----------+

The device address itself can be either “public”, in which case it must adhere to the IEEE 802-2001 standard, and is generally baked into the radio. Alternatively, it can be randomly generated, in which case it can change across power-cycles, and a single radio may even have several addresses. All the nitty-gritty details about device addresses can be found in Bluetooth Specification Version 4.2 Vol 6, Part B, section 1.3.1.

Implementation details

Typically, a microcontroller application has exclusive access to the Bluetooth radio. That’s because it is generally the only application. Not so with Tock, which runs multiple totally independent processes. The Tock Bluetooth Low Energy driver needs to somehow support multiple processes, each potentially want to advertise their own data.

The restriction we care about is that processes cannot interfere with each other. It turns out that as long as we control the specific timing and source address of Bluetooth advertising packets, we can do that without imposing much restrictions on applications. This new driver treats each process as a separate, virtual, Bluetooth Low Energy device.

On the surface this ends up being a pretty simple interface. When a process initializes BLE advertisements, the driver creates a new device address for the process. The process then configures parameters, such as the advertisement interval, and the data to advertise, and starts advertisements. All of this meta-data is stored in the process’s grant section—a heap specific to each process that is only accessible to the kernel and allows the kernel to dynamically allocate memory without compromising overall system reliability.

When it’s time to perform an advertisement for a particular process, the driver simply copies the source address and advertisement data into the radio’s transmit buffer, sets Bluetooth Low Energy specific radio configuration and transmits. But how do we keep track of when to perform each process’s advertisement?

If we only had to worry about one process, we would simply setup a timer that fires every advertising interval. In this case, where we need to service an arbitrary number of processes, we do the same thing, but with a virtual timer for each process, also stored in the grant section.

For each process, the driver keeps track of the advertising interval as well as the time of its last advertising event. As soon as it finishes an advertising event, the driver looks through the processes, computes which advertising event is next, and sets a shared alarm to fire at that point.

When the alarm fires, the driver knows that it needs to perform an advertisement for some process, so it, again, looks through the processes to find which process the alarm was initiated for, and advertises on its behalf.

It’s possible for processes to have overlapping advertising events. In practice this is rare as the driver adds an additional random delay between advertising events (as required by the Bluetooth specification). Nonetheless, collisions are sometimes unavoidable, and in those cases, the driver simply chooses one process to advertise for and re-schedules the others. In principle, it could be possible to prioritize processes that have advertised least recently, but we have not yet implemented such a mechanism.

Let’s see a demo!

So how can you actually use this?

Below is code for a Tock process to advertise a device name every 100ms. I programmed this process on a nRF52 development kit, alongside three others with slightly modified names, and set to advertise every 300 ms, 20 ms and 1 second, respectively.

int main(void) {

uint16_t advertising_interval_ms = 100;

char* device_name = "TockOS1";

// configure advertisement interval

ble_initialize(advertising_interval_ms, true);

// configure device name

ble_advertise_name(device_name, strlen(device_name));

ble_start_advertising();

return 0;

}

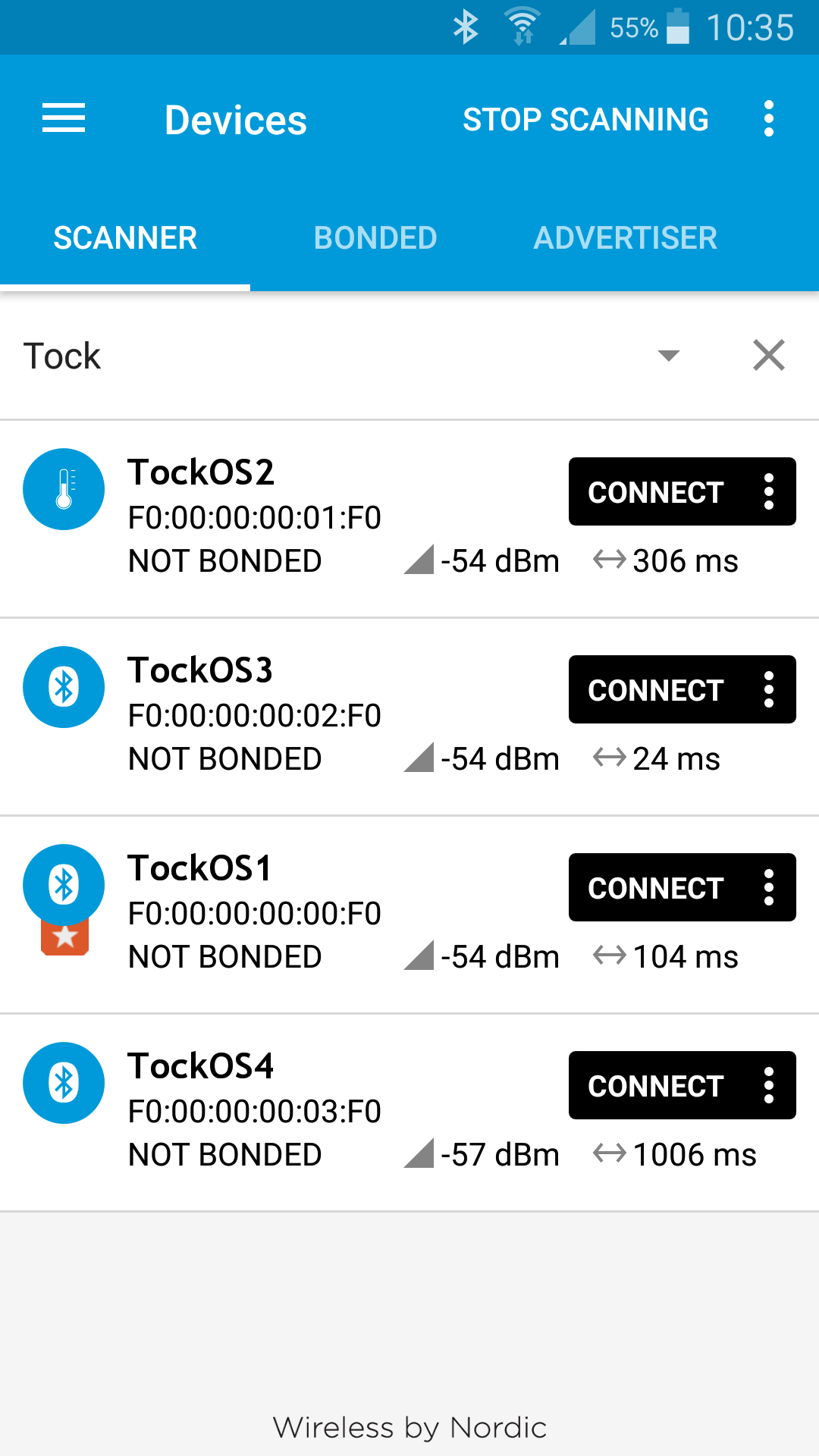

Looking at a screenshot from a Bluetooth sniffing application on my phone nRFConnect, we can see all four processes’ advertisements:

Notice that the kernel generated a unique static random device address for each device (the device address is currently based on the process identifier). The intervals, in the bottom right corner of each row, show the advertising intervals the app on my phone calculated, which roughly matches the intervals I set up in the Tock processes.

Try it out

The driver is now merged in the Tock master branch and runs by default on the NRF52DK board. The applications I used in the demonstration can be found here